Researchers May Have Finally Identified The Cause Of Crohn’s Disease

For the 565,000 Americans who suffer from Crohn’s disease, the inflammatory bowel condition that causes abdominal pain, diarrhea, weight loss and fatigue, promising new research could mean better treatments are on the horizon.

The authors of the study, published in the journal mBio, identified a fungus and two bacteria that may be responsible for the development of Crohn’s. Researchers are optimistic that this new information will help them design better therapies to tackle the disease.

What’s In Your Gut?

The study looked at the bacterial makeup of patients with Crohn’s disease, healthy family members of those patients, and also healthy strangers with no Crohn’s in their families. Researchers compared the gut profiles of those with Crohn’s disease to those living in the same household with similar genes and diets, which are also contributing factors to the development of the disease, as well as to the individuals with no family history of the disease.

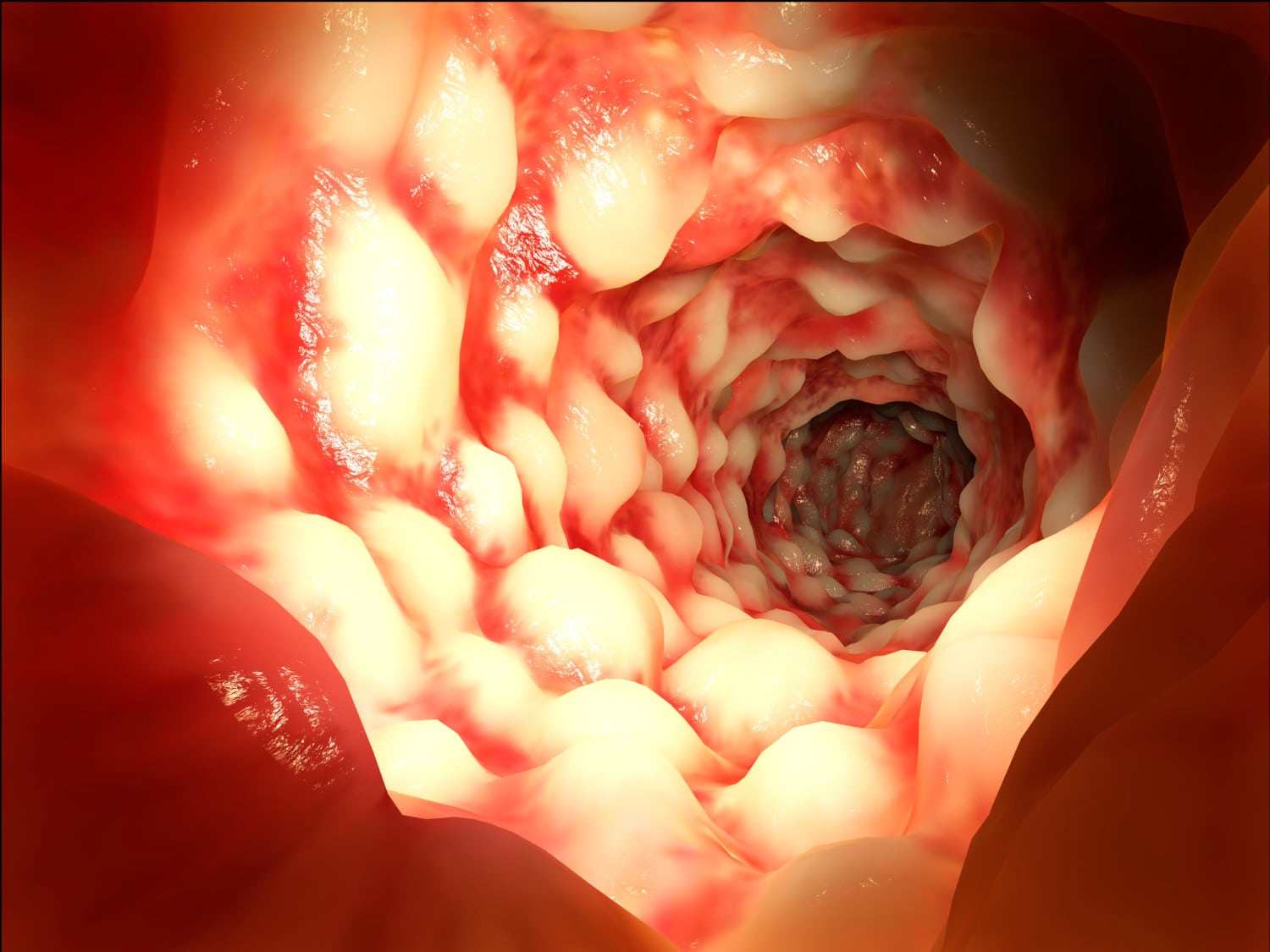

When analyzing fecal samples, they found high amounts of E. coli, Serratia marcescens and Candida tropicalis in the patients with Crohn’s — significantly more so than in the other two groups.

RELATED: Well, It Turns You Might Need Your Appendix After All

Dr. Mahmoud Ghannoum, a professor and director of the Center for Medical Mycology at Case Western Reserve University and lead author of the study, explained in a press release:

“We already know that bacteria, in addition to genetic and dietary factors, play a major role in causing Crohn’s disease. Essentially, patients with Crohn’s have abnormal immune responses to these bacteria, which inhabit the intestines of all people. While most researchers focus their investigations on these bacteria, few have examined the role of fungi, which are also present in everyone’s intestines.”

So, What Does This New Research Mean For Those Suffering With Crohn’s?

Ghannoum went on to explain the potential significance:

“Our study adds significant new information to understanding why some people develop Crohn’s disease. Equally important, it can result in a new generation of treatments, including medications and probiotics, which hold the potential for making qualitative and quantitative differences in the lives of people suffering from Crohn’s.”

This is the first time the bacteria Serratia marcescens and the fungus Candida tropicalis have been identified as joining E. coli in contributing to the disease. Additionally, the researchers found that the presence of beneficial bacteria was significantly lower in the Crohn’s patients, backing up previous research findings. They also noted that there were significant similarities in the “gut profiles” of the Crohn’s-affected families that were very different from the families with no Crohn’s. Ghannoum does urge caution when interpreting the new information:

“We have to be careful, though, and not solely attribute Crohn’s disease to the bacterial and fungal makeups of our intestines. For example, we know that family members also share diet and environment to significant degrees. Further research is needed to be even more specific in identifying precipitators and contributors of Crohn’s.”

Additional studies will be necessary as part of the process of designing new treatments based on this information, but those suffering from the condition will take heart that researchers continue to make progress.