Scientists extract plant DNA from 2,900-year-old clay brick

Scientists have found another key to unlocking part of our planet’s history, thanks to a discovery made inside a nearly 3,000-year-old brick.

According to the research report published on Aug. 22, a team of scientists extracted plant DNA from a crack in an ancient clay brick originating from a palace in Iraq from 2,900 years ago (883–859 BCE). From that DNA, test results showed the existence of 34 unique plant groups.

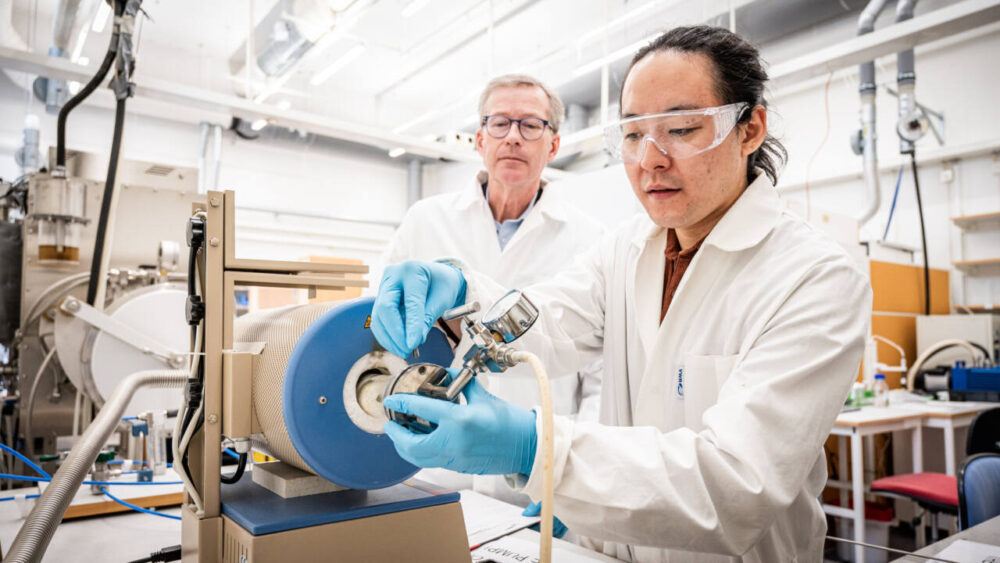

“We were absolutely thrilled to discover that ancient DNA, effectively protected from contamination inside a mass of clay, can successfully be extracted from a 2,900-year-old clay brick,” Dr. Sophie Lund Rasmussen, one of the study’s authors, told Phys.org. “This research project is a perfect example of the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration in science.”

MORE: Painting suggests people in Pompeii ate a pizza-like dish

The extracted DNA showed evidence of various plant families, including cultivated grasses, heather, cabbage, birch and laurels. In the study findings, the authors expressed surprise at how well-preserved the DNA samples were despite their advanced age. The team attributed the samples’ lack of biological contamination to how the brick dried in the sun and wasn’t burned in fire. This allowed the genetic material to stay preserved in the clay.

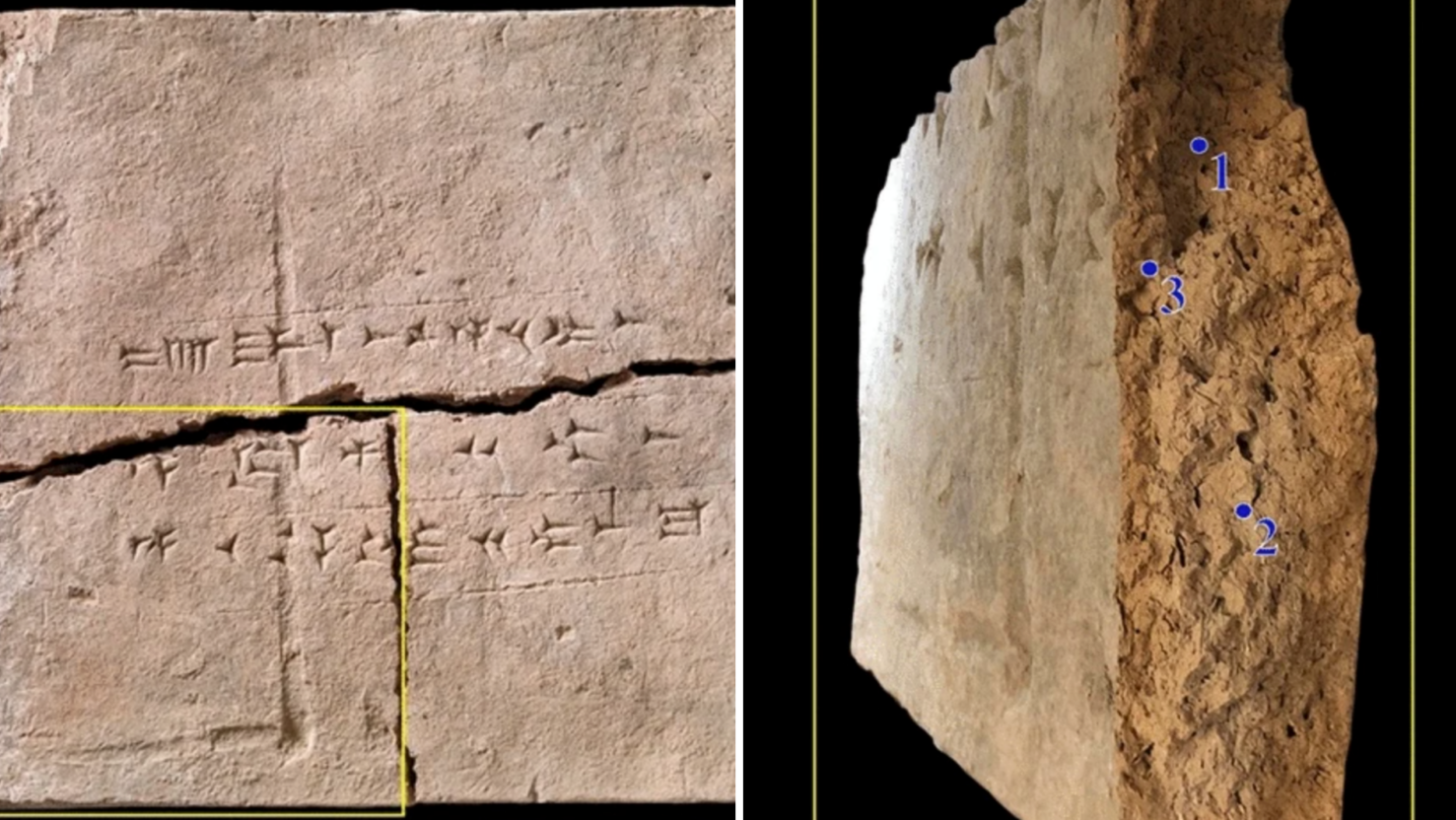

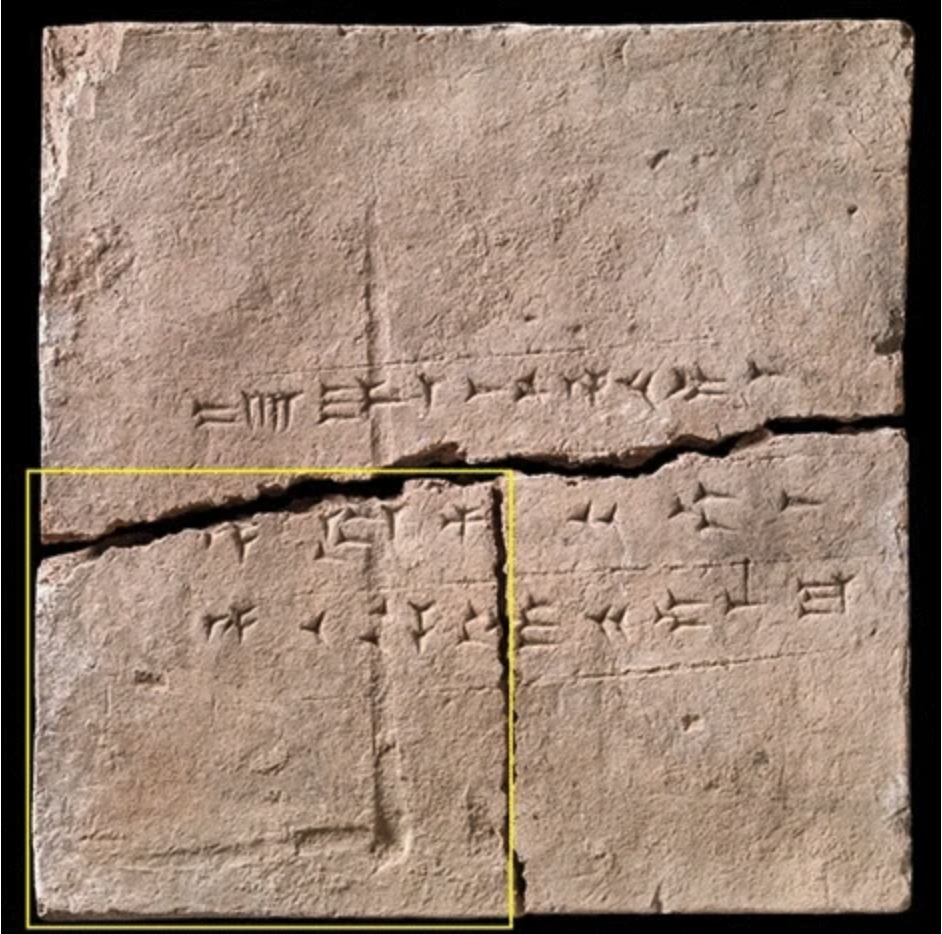

Determining the brick’s age came down to studying its engravings, which scientists said was a form of cuneiform writing in a now-extinct Semitic language called Akkadian. The inscription said, “The property of the palace of Ashurnasirpal, king of Assyria.” That helped the research team narrow the artifact to a specific historical time.

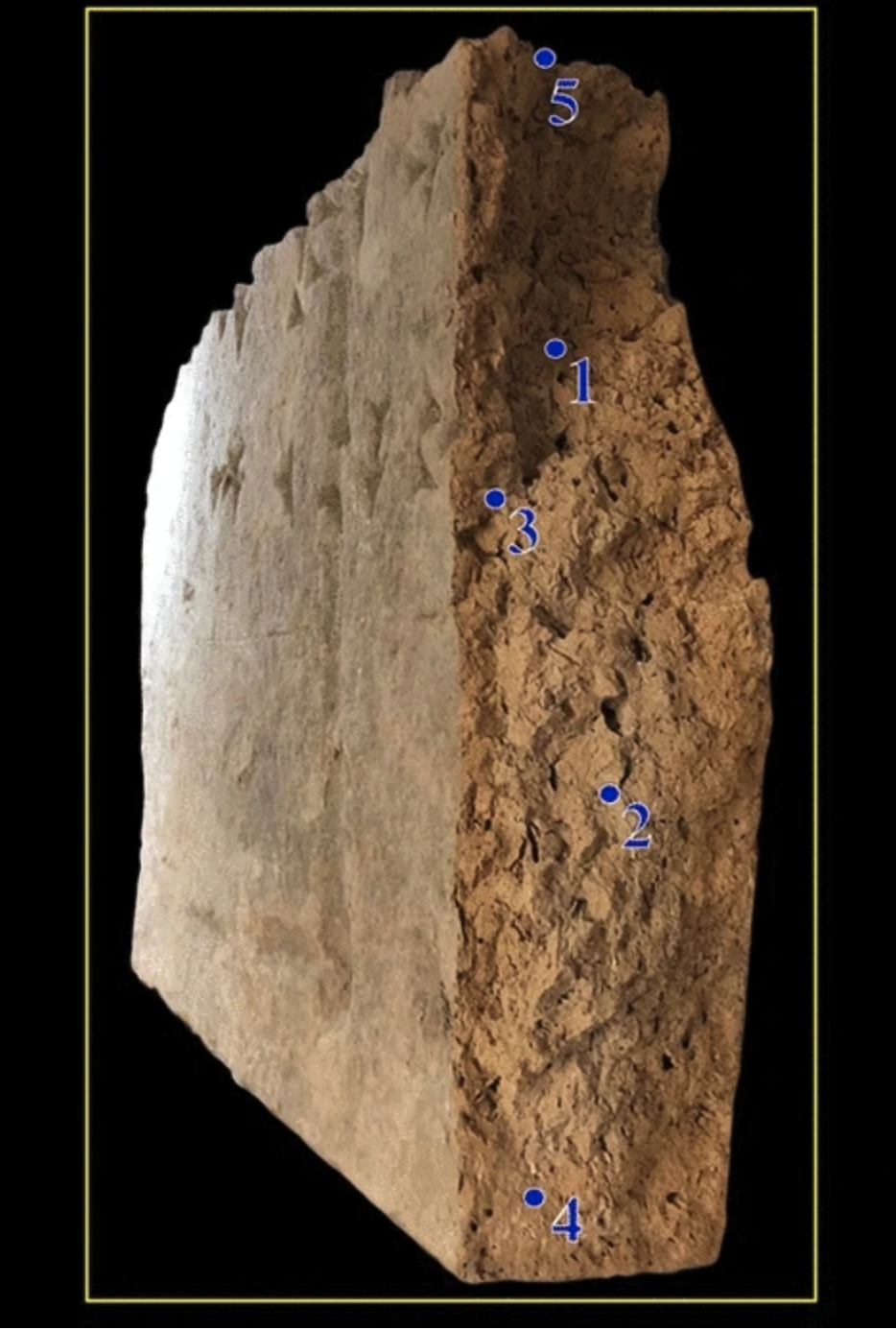

The extraction of the sample material came from one of the cracks in the hardened clay and obtaining smaller core samples to minimize visible and structural damage to the brick.

MORE: Archaeologists discover a 5,000-year-old tavern with food still in bowls

The newfound data from the study lays the foundation for new research methods and examination of biodiversity over centuries and millennia. It will help scientists compare and contrast plant and animal life to better help them understand how they disappeared or have evolved.

The new research methods used in the study can also help scientists unearth evidence from other ancient materials in the future without doing noticeable, permanent damage to priceless artifacts.